Multi-Genre Research Projects

Multi-Genre Research Projects

An MGRP is, first, a research project. This is not, however, a crusty research paper. Traditional research papers often regurgitate information, while MGRPs synthesize multiple sources and creative writing to generate a whole much larger than the parts. What is created from the research is where the magic happens. The idea of the MGRP comes from Writing with Passion by Tom Romano (1995) - a book I first read in Dr. Aaron Levy's class at Kennesaw State University. Romano's book is all about non-traditional approaches to student storytelling, literacy practices, and research. With chapters about truth in writing, relationships, ways of knowing, and being blissfully lost in literature, this book is a powerhouse for English teachers seeking to deepen student connection to both reading and writing. Arguably the most potent component of the text is the presentation, discussion, and analysis of the MGRP.

Students select a research topic, conduct research, and then write five original creative pieces in different genres that represent what they've discovered. Each artifact has a "notes" page - this explains their metacognitive thinking on the "why" behind each piece, including their genre choice, research used, and their desired effect and contribution to the whole. Their finished projects have a letter to the reader, a work cited page, and a table of contents. Let's break down how all this happens.

First, students pick a topic. I had my students write up a formal research proposal with research questions. I tasked them with explaining why the issue was important to them, and how it was connected to their own lives. In the words of my doctoral advisor at Georgia State, Dr. Caroline Sullivan:

"Your research topic should be something that you go to sleep angry about or wake up thinking about. It should be something you can talk about all day and never get tired of it."

Once students submitted their proposals, we began researching. This is part of the project I had messed up in years before: either I didn't require students to study deeply enough, or I didn't have students construct clear research trails. This year I had students create their MLA citations for each source before moving on with the project. I wanted it to be crystal clear that their creative writing, no matter how innovative, had to be centered on research.

The next step is writing. This is a challenge that Romano (1995) writes about extensively in his chapter on "Problems, Issues, Dilemmas" with the MGRP (pp. 133-147). There are, in fact, many problems, issues, and dilemmas with this work. It's messy any time you are in the river with students (Nelson, 2004).

Tough Questions

How do you ensure students are writing?

How authentic are they being?

How do you help them move past their "school" thinking and get into a genuinely creative space?

How will students work together if they are all working on different genre pieces? I mean, letter writing is not the same as writing a poem. How do I "teach" this?

What are their deliverables or formative assessments?

How will timing work?

Romano (1995) answers many of these questions in his book, as does Nelson (2004), because this project requires a writing culture in your classroom. This cannot be done as a "stick your toe in" kind of work, as Dr. Levy said many times in our class together. As I have now found, this is about creating a space for writers - that means workshopping, reading, sharing, and being a community of writers. This must transcend being students, sitting at desks, doing school.

A structure that helped us do this work was the mixture of writing, workshopping, and presenting our writing in chunks. A workshop model where students work in groups to share and get feedback on their writing as a regular process is vital to both accountability (student to student) and growth. Students should get to a point where they do not want to "let each other down" when they come to the workshop by not having drafts to read. Students should share their drafts (I sometimes call them "ugly drafts") regularly. We use a "praise, question, critique" model, and the authors record their feedback and make revisions; more than that, this offers an opportunity to talk through their thinking and get new ideas.

We also incorporated Nelson's (2004) feather circles into the rotation. These are opportunities for students to share their "publishable" pieces in class by reading them aloud in a sharing circle. We call them feather circles because we pass around a feather stick while we read - whoever holds the stick shares and then passes the stick. No other talking is allowed. This is not a place to qualify your choices or explain your writing. This is not a place for feedback. This is a place for listening and sharing the finished pieces writers have completed. Feather circles are a form of publication; the best part is the thank you notes.

After each feather circle (we did about 3 of them during the MGRP), students pick their favorite pieces to respond to with a deep thank you note. They are encouraged, after modeling, how to write about specific moments or lines in an author's piece that spoke to them and connected with them on a personal level. The "why they enjoyed it" takes some practice writing about.

Through these cycles of writing groups and feather circles, students completed their full MGRPs in about a quarter of a semester. We did a "dear reader letter," and the work cited page together as a whole class. I spent the rest of the time modeling my own writing, discussing problems, setting goals with students, coaching, helping to remove roadblocks, and writing alongside my students. I do very little instruction during this process; I'm a coach and a mentor most of the time.

How does it help students write more authentically?

Student choice might be the most crucial facet of making the MGRP meaningful. Regardless of what kind of product a student creates, the research notes connect the creation and the reader. In these notes, students are forced to delve into their metacognitive thinking and reflect on their choices. Some students choose to make music, art, or even video dance routines. The notes accompanying each piece must speak to the "why" behind their choices and explain the thinking that went into their decisions. The author must explain how their research informed each piece and even each decision they made in crafting their work. In the "real-world," writers research: books, articles, stories, songs - research makes the written world come to life. This project centers what real writers do.

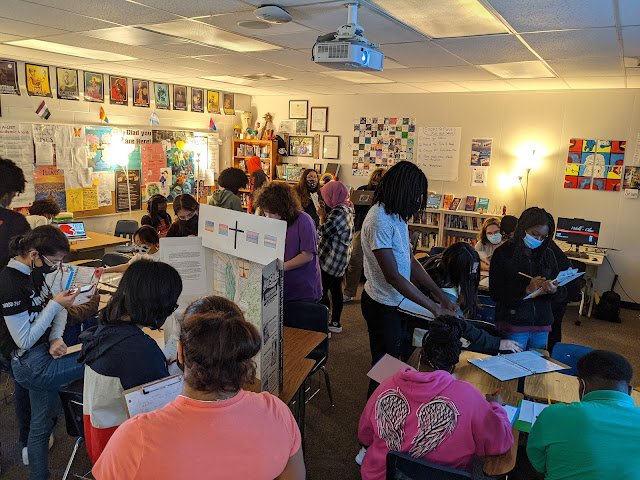

Students are also writing for a larger audience the entire project - it isn't just about the teacher. Rarely do I get involved in evaluating or giving feedback on student writing in any phase of this project. Because students have been doing feather circles and writing groups for weeks beforehand, they are accustomed to writing for their peers. It is an audience that gives them feedback - not the teacher. They know that these creations will live on in the classroom or even the community. To return to the afternoon I mentioned at the start of this writing, the gallery walk was the ultimate feather circle and provided a very real audience for their peers, teachers, and administrators to come in and view their projects. While I didn't invite any admin this time, it is a great opportunity to showcase authentic passion, joy, and meaning which can only come from authors having choice and agency over their craft; they are so much more than students.

Students are encouraged to always consider their audience, purpose, and the speaker in each piece throughout the process. Real writers always write for more than a grade. Because this is creative writing, students can take their research and incorporate it into original writing from anyone involved in their topic. Researching Black film? Write a letter as a Black actor, or even better, write a resume as a Black actor trying to get work in predominately white spaces. Want to learn more about a favorite serial killer? Write some poetry based off of their journals or recorded footage from their perspective. Things can get really intense. I had several MGRPs that made the hairs stand up on the back of my neck while reading. This kind of authentic writing simply couldn't happen in a research paper where facts go to die. In the MGRP, they come to life.

Conclusion

If you have any questions about the MGRP process or would like assistance in having anything discussed in this article, I'd be happy to help. I don't have all the answers - I am figuring things out every day, every year, just like you. I can proudly say that I try to create space for students and their voices, dreams, and creativity in our classroom. I can say that this is so much more than doing school. I can say that this project is more rigorous than any basic research paper could ever dream of being.

Comments

Post a Comment